The Problem with Models

The rules of causality and reason, by which the universe apparently operates, are represented as models. The apparent order of phenomena in reality is condensed into an abstract representation in an attempt to predict and offer insight into reality. However, human actions seem particularly resistant to models. There are a plethora of models postulating the possible nature of human, human’s end, and the nature of societies, but they conflict with each other. Through this dialectic, a new model is made, perhaps closer to the objective truth, but the model, being an entity in the intelligible world and not the sensible world, can never encompass complete objective truth. Though models are undeniably useful in understanding reality, we must consider the limitations of models and the consequences of our models failing.

A model is an abstraction of reality, hence necessarily simplified and incomplete. A model represents reality through rules or equations. Every model is limited in that, when we make predictions using a model, we always assume that the future will behave like the past, which cannot be proven. This is particularly true of human interaction as society changes at a rapid pace. Furthermore, when we interpret reality to make our models, we cannot observe all of reality; we often have limited data to base our assumptions upon. Again, this is especially true with human interaction as we do not have a controlled environment. Instead, our data comes from history and hence our assumptions in the model cannot be proven to be true in general. The model is always limited, but it can be a powerful tool for understanding and predicting phenomena. Just as we try to create a standard model of the universe in an attempt to understand and predict physical phenomena, we create a social model in attempt to understand and predict human action.

In the 17th century, many models for society were based upon the individual. The fundamental nature of humans was taken as an assumption, from which social values were derived, for example the Hobbesian state of war, or Locke’s state of nature. The models of society arose from theories of human nature, but the theories of human nature varied widely. In the 19th century, a paradigm shift occurred wherein the state of human nature became dependent on society. Marx famously says, “It is not the consciousness of men which determines their existence; it is on the contrary their social existence which determines their consciousness.” Thus, the nature of man is determined by society. The causal arrows of the model were reversed completely. This nature versus nurture debate relates to Berlin’s notion of positive and negative freedom: the individual can be free from interference and act on his own nature to form society, or the society can nurture the individual to be his own master. Does the society determine the people, or do the people determine the society?

The choice of social model is critical. Governments, the structure of societies, are formed with these models. In fact, Marx believes that the purpose of creation of the models is to induce change: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” The very belief in a model is potent enough to change how one thinks and interprets reality since a model employs a mode of thought. Marx says, “The materialist doctrine that men are products of circumstances and upbringing, and that, therefore, changed men are products of other circumstances and changed upbringing, forgets that it is men who change circumstances and that it is essential to educate the educator himself.” Our beliefs in models, which derive from our circumstances and our education, change society and hence other men. For Marx, the abstract model is tool to change reality.

Marx’s idea of commodity fetishism is precisely such. Economics assumes that each individual desires to maximize economic value, that is, money. Then economic policy is implemented to maximize the wealth of the nation. The capitalist model assumes people want to maximize money, so when policy derived from this model is implemented, it will work most effectively when people actually pursue money as an end, thus people and governments will encourage such behavior in order for successful implementation of the policy. The result is that people seek money as the end, the objective marker that holds value. Hence, the implementation of a capitalist economic model has the propensity to induce consumerism. The implementation of theory affects how people act in practice. From this arises a great limitation in modeling human actions; societies are rarely static. A society changes through time, and old models lose accuracy. Interestingly enough, the creation of a model itself refashions society so that even more models are required as old models become outdated. The truth that the model tries to understand is changed by the adoption of the model itself.

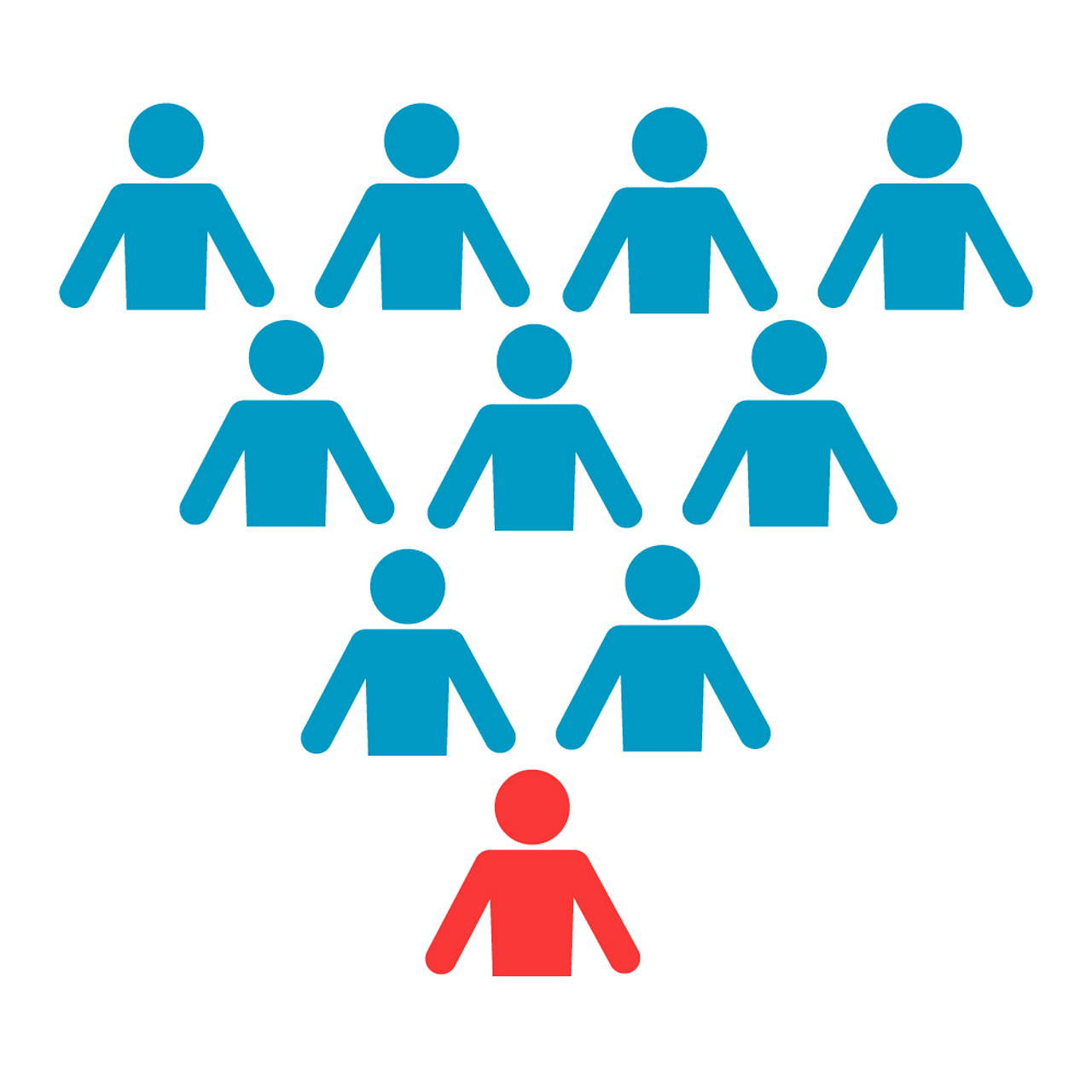

The adoption of a model can induce significant change and as such, we must be wary of the limitations of the model. In models wherein citizens determine the society, the resulting society is hard to predict, as citizens do not act uniformly. Free agents with negative liberty leads to chaos, in the sense that, the web of interaction between free agents is complex and unpredictable. In models wherein the society determines the citizen, the goal is to create an ideal society, which in turn will create ideal citizens. Observe that once the model is based on the society, the success of the society becomes the end and not the success of the individual. The nature of this social model is to institutionalize, as individuals become a means to further the end of the institution. Of course, it is quite subjective whether the individual is more important or the collective, but pursuing the collective end requires the pursuit of a model society. Berlin says, “If we are not armed with an a priori guarantee of the proposition that a total harmony of true values is somewhere to be found, we must fall back on the ordinary resources of empirical observation and ordinary human knowledge.” The model has no guarantee of success.

Despite this, subscribing to a model that describes an ideal society remains attractive. Institutions have explicit goals and explicit paths to success within the models. There is security in belonging to an institution. Furthermore, even if an institution inhibits negative freedom, there is the stoic strategy of “retreat to the inner citadel.” The model has an objective, where if all the assumptions are correct, and all goes as planned, a utopia of sorts will be reached. A model with an assumed system of values, that is positive liberty, seems much more likely to achieve this utopia than the chaos of free agents all attempting to determine the objective of the society. However, Berlin is quick to warn, “This goes back to the naïve notion that there is only one true answer to every question: if I know the true answer and you do not, and you disagree with me, it is because you are ignorant; if you knew the truth, you would necessarily believe what I believe; if you seek to disobey me, this can be so only because you are wrong, because the truth has not been revealed to you as it has been to me. This justifies some of the most frightful forms of oppression and enslavement in human history.” In addition to the chance of the model failing, there is the possibility of the model being perverted. The silencing of the dialectic and the rule of one model is prone to unseemly manipulation. Positive freedom assumes a single set of values, but Berlin claims that there is a value pluralism, that is, “human goals are many, not all of them commensurable, and in perpetual rivalry with one another.” As such, one model cannot encompass the range of human behavior.

The problem arises when we believe that only one model exists, that there is one ideal for all of humanity. We must break from the monolithic model. Value pluralism calls for a mirroring model pluralism. There is a symmetry between human and natural phenomena. Humans each desire their own goals, and every human has different goals which are sometimes in conflict with each other. Similarly, natural phenomena have their own models and each phenomena has its own model which are sometimes in conflict with each other. Furthermore, no model is truth by itself, just as there is not one ideal for all of humanity. Sartre poignantly says, “existence precedes essence.” For Sartre, life has no meaning a priori, but rather the individual creates his own set of values through action. We have seen that man creates models and that the implementation of those models can affect individuals, perhaps by changing their values. We each influence one another, which Sartre calls intersubjectivity: “this is the world in which man decides what he is and what others are.” We can freely create our own natures and break from any model imposed upon us. Let us then extend the mirror between human goals and models. Just as one human’s goals influence other humans’ goals, a model influences other models. Disciplines of science inform each other, much like a humans’ goals inform other humans’ goals. It is a dialectical process with thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. At this point, we have come full circle to Marx and his belief in Hegel’s dialectics. The synthesis creates a better model, which may appear to be the absolute model. However, as models are necessarily limited, we once again go through the cycle.

In order to have a social model that is watertight, we need to understand the human decision making process itself. Such efforts are being spearheaded by neuroscience and psychology, though a complete understanding seems very distant. Even if the universe followed a set of laws, the number of particles and their interactions would give rise to emergent unpredictable behavior. Despite our quite comprehensive understanding of physics, we are unable to predict weather accurately beyond a week because of its complexity. Likewise, the sheer number of neurons likely gives rise to incredibly complex phenomena, and we would require individual limited models for different phenomena in the brain. This highlights the eternal limitations of models, that even if we have the correct model of the universe, it will lead to complex behavior, complex enough that they demand their own models. These secondary models are limited in that they do not contain all the information of the first. Ultimately, the abstract networks of reason and causality that we create can never encompass the universe. All of our models are perpetually limited and can never be proven to be objective truth.

Models give us a false impression of complete understanding. We want to live under these models, because it is simpler. Goals, rules and hence, the path towards success are explicit. For the most part, the advanced models we have developed, accurately portray reality. But models are not truth, or else one model would reveal the fallacies inherent in the every other model. Instead the dialectic of these models reveals the fallacies of each theory. Then whatever we choose to be the prevailing model is the model whose fallacies we are most ignorant of. Models are useful for making predictions that inform an action, but since the model is limited, one should not live by a model. In fact, even the mere implementation, or belief of a model affects thought. These models inform our conscious, but it would seem that we cannot live solely by a simple universal code of ethics or a universal meaning of life, for these models are perpetually limited.