It's All About Perspective

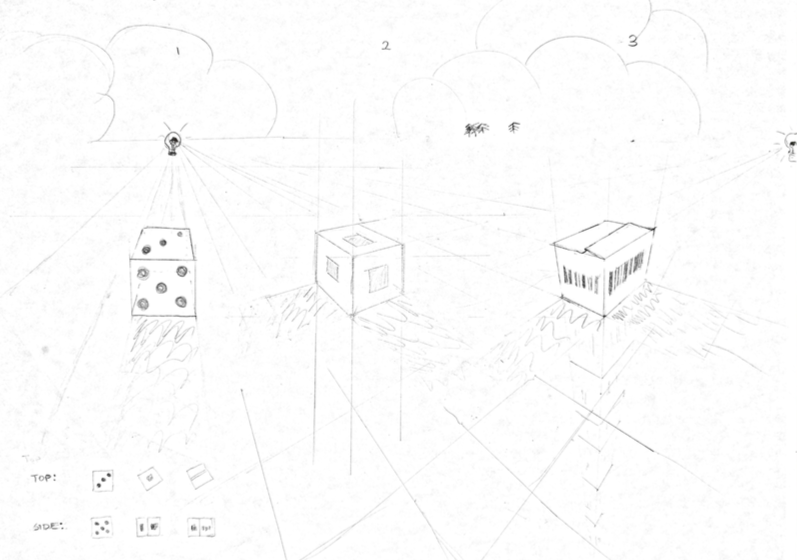

The photo of a railroad disappearing into the distance at a singular point is a classic image that demonstrates the intuitive notion that farther away objects appear smaller. We can be even more precise and say that the apparent size is directly proportional to the distance, that is, a ten foot tree will appear the same size as a twenty foot tree that is twice as far. Similarly, in the photo, we could count the pixels between the two rails and find a point x, where the track has narrowed by 50% compared to point y. x would indicate a point that is twice as far as y. If we knew how far some point in the tracks was, we could calculate the distance of any other point along the tracks, just from a photo. There are other interesting properties to consider in the photo: we a see a singular vanishing point at which the parallel rails converge. I have drawn some boxes with one, two, and three such vanishing points.

The first box resembles the railroad track with one vanishing point. The second box’s edges, if extended, will converge to two vanishing points on the left and right. Finally, the third box’s edges converge at three vanishing points. An interesting question to consider is how many vanishing points are possible in a picture?

To answer this question, consider any two parallel lines in the scene. If they go away from the viewer, they will become smaller and smaller, creating a vanishing point. You could imagine yourself having an infinitely long arm, and wherever you pointed your arm, you would create a vanishing point as your arm disappeared into the distance. Thus, with an infinite number of directions to point your arm, there are infinitely many possible vanishing points.

This is perhaps surprising because the terms one point perspective, two point perspective, and three point perspective imply that the number of vanishing points is strictly dependent on the position of the viewer. But by placing a railroad track in your scene, you could add another vanishing point and so the number of vanishing points is also scene dependent.

Now imagine that you are facing a long wall (the wall runs from East to West in front of you and you are facing North). Clearly, the East and West ends of the wall are farther from you than the bit of wall directly in front you, so would the wall appear to taper at the sides? If you photographed such a wall, would the walls be shorter on the sides?

Images are produced by projecting a scene onto an image plane. In the images we have discussed, distant objects appear smaller, which is true to life. But what if I drew objects such that they always stayed the same size?

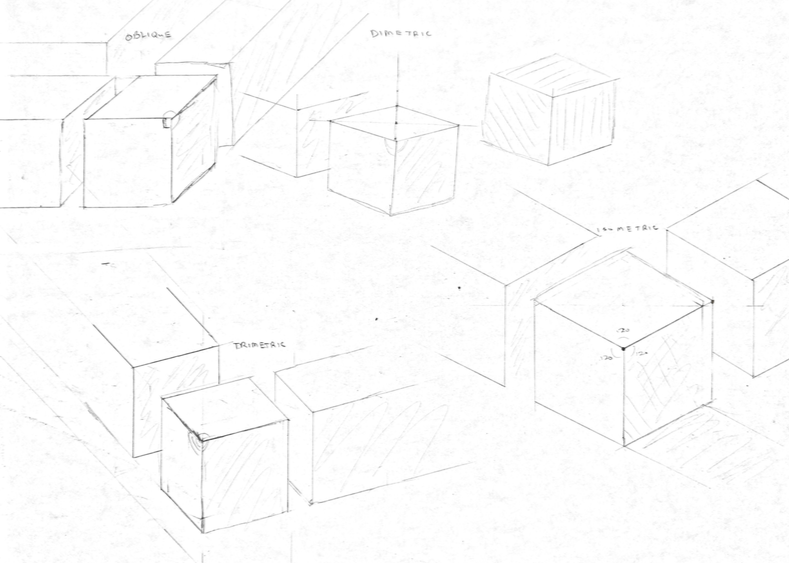

There are four projections in the image. Notably, cubes farther away from the viewer are rendered with the same apparent size. A railroad in these images would not vanish to a point. In fact, we see that all parallel lines are preserved, and so there are no vanishing points. The fact that apparent size does not change with distance means that we could measure objects in the image accurately if we knew some distance in the image. Thus these projection are useful for maps and technical drawing. These projections, save for the top left “oblique” projection, are also equivalent to viewing a scene infinitely far away with infinite zoom. This makes sense as an object 1,000,000 feet away from you and the same object 1,000,000 + 1 feet away from you is only .0001% further away and thus .0001% apparently smaller. Where as an object 1 ft away from you appears half the size 1 + 1 ft away. In photography, zooming in has the effect of “flattening” an image, which we can now formally describe as preserving apparent size despite distance between objects.